The 'Inside Out' Project

by Mary Featherston

Can the physical environment be a ‘teacher’ in itself?

A brief report of a research and design project to investigate the relationship between pedagogy and design of the physical environment. This project involved the refurbishment of a combined Grade 5/6 Unit within Wooranna Park Primary School, equivalent in area to six traditional classrooms. Support from the Victorian Department of Education provided a most unusual opportunity for an extended collaboration between an interior designer and a school with a long standing commitment to radical education reform. The ‘Inside-Out’

Project set out to investigate a number of vital design questions:

- What is the role of the physical environment in contemporary schooling?

- How can design support a dynamic, responsive approach to learning?

- Is it possible to create an amiable, aesthetic environment which is also full of rich and complex possibilities for learning?

- What is an effective participatory design process?

“Design for such a complex and dynamic situation as contemporary learning and teaching requires that all physical elements: built space, furnishings and loose items, be considered together to create a functionally and visually harmonious environment. The new environment provides a diverse rather than a totally flexible environment and an inseparable relationship has been created between pedagogy and design. Students and staff welcome the conviviality and purposefulness of their Unit and treat it with care and respect. This attitude is possibly a response to the respect given to their involvement throughout the design process. The project has explored many questions but it has also raised many more. There is a crucial need for further development and evaluation. Education must come to be recognised as the product of complex interactions, many of which can only be realised when the environment is a fully participating element. ”

In this case, breaking out of the straight-jacket of conventional ‘box-like’ school planning is part of a continuum of radical change that has taken place in the school over many years. Innovations in pedagogy and the physical environment have grown out of contemporary understandings about children and learning and from the school’s strongly-held belief that children have a right to the highest quality social and learning experiences.

BACKGROUND

Schools are one of the most interesting and challenging areas for design today.

Young people spend vital hours of their lives in them, they are the workplaces of many adults, they contain many relationships and huge expectations and they absorb vast resources. School buildings are very visible and tangible expressions of our attitudes to children and learning.

Locally and internationally there is a growing consensus that traditional formulas for school and schooling – separate classrooms, minimally furnished and strung along corridors are no longer appropriate.

RATIONALE

Creating a new school – or even a modest refurbishment such as this, is a creative project involving many choices. In the absence of precedent or familiar formulas, what determines the choices that are made and who should make them?

In this case, choices were determined by the principles and values as set down (and continually reviewed) in a guiding document – the school’s ‘raison d’être’. This document links beliefs about children, learning and the role of school in society to pedagogical practice – the organisation of people, curriculum content and time.

It also provided a firm basis for organisation of space, furniture and loose items, i.e. design.

For example, where curiosity is seen as the spark that drives the processes of learning, the environment must provoke wonder, exploration, expression and reflection: and where learning is seen as both an individual and a social process – construction and co-construction of meaning, the environment must present rich possibilities for relationships and learning in a wide diversity of groupings and settings. Children and adults must feel comfortable and be able to easily negotiate the environment with clear circulation paths and easy access to materials and tools. All settings should be always available – not waiting for next scheduled session in a specialist facility. The quality of each experience will be enriched by the integrity of the activity settings – how effectively they support each activity, provide cues for appropriate use, enable interaction, minimize distractions, etc.

The traditional classroom is tightly designed to support teacher-focused learning by minimizing distractions – hence their blandness. Here, the role of the physical environment is not as a ‘teacher’ in itself (it does not provide stimulus or interaction) but acts to focus attention on the teacher and the largely one-way flow of communication. Such classrooms are found all over the world and are deeply familiar to us all, which makes it difficult to envisage alternatives.

“Our children need an educational environment that fires the imagination, develops good citizenship and promotes a lifelong thirst for knowledge. If children are to maximise their learning, then their school must be a place of optimism excitement and challenge, where students and teachers see each day as a journey, full of purpose, and where intellectual engagement and connectedness to the real word are priorities.”

THE PROJECT

The intention of the ‘Inside-Out’ Project was to refurbish an area within a Victorian government-funded school, to support and reflect contemporary understandings about children and learning. The design process was to include all the participants (students, staff, parents) and to seek design solutions that might have broader applicability. Support and funding was given by the Victorian Department of Education and Training in 2004 and the refurbishment was completed, with additional funding from the selected school, in mid-2005. In order to develop and test ideas it was considered important to select a school where the educators were already committed to and experienced in implementing educational innovation. Wooranna Park Primary School (WPPS) was selected as a most suitable site. Over many years, the Principal, Assistant Principal and staff have rigorously investigated educational theory and practice, in Australia and internationally. Their belief that children have a right to high-quality learning experiences has led to the development of innovations in pedagogy and physical environment. The school has received recognition in many forms and is respected by many educators.

The school is a typical light timber construction (LTC) built 35 years ago. Since 1996 internal walls have been partially removed and non-institutional furniture introduced to create environments for active, collaborative learning and to promote democratic relationships between children and adults.

Despite extensive modifications, one area of the school was not functioning as intended – a combined group of 100 Grade 5 & 6 students in the space of 6 typical classrooms. This large, open area was furnished with tables and chairs and teachers were finding it difficult to provide for a wide variety of experiences and groupings. Also, a lack of suitable furniture failed to promote student autonomy. Openness and flexibility of the space made it difficult to present traditional teacher-focused sessions or the more collaborative, team-teaching approach favoured by the school. But, importantly, the informality of the spaces and furnishings did provide a colourful, inviting home for the large group of children. So, this Unit was chosen as the site for re-design as it posed significant and relevant design challenges. The scope of design was to consider all ‘layers’of the physical environment: existing built spaces, furnishings and loose items to create a functionally and visually harmonious environment. Unfortunately the budget did not extend to opening up external walls for a seamless indoor/outdoor learning environment – much desired by the children.

THE PARTICIPANTS

School Leaders Principal, Ray Trotter is widely acknowledged as a committed and courageous educational reformer. He has been Principal of WPPS for 19 years and has two grandchildren in the school. Esme Capp, Assistant Principal has taught at WPPS for 22 years and has worked closely with Ray Trotter in the development of pedagogy and practice. She has since completing a PhD at Monash University ‘A case study of a contextual participative model of a school.’ Esme has two children attending the school.

Students

A combined group of approximately one hundred 10-12 year olds, as diverse in ethnic and social background as they were in height and shape – a design challenge in itself. With few exceptions WPPS was the only school they had attended.

Staff

A team of four full-time teachers and 2 part-time aides who had been working together in the Unit for 4 years. This team has remained substantially the same for several years and they have a strong commitment to, and enjoyment of team teaching. Their backgrounds and training are also diverse, including secondary as well as primary, arts and science training.

School

The school is situated in a suburban neighbourhood 30 km from Melbourne. It comprises approximately 370 students from Prep to Grade 6, over 40 nationalities and a wide variety of social backgrounds – it is classified as a category 9 school – highest level of social disadvantage. The original building had the typical layout of long central corridors and square classrooms opening off each side (double loaded corridor).

Designer

Mary Featherston is an interior designer with many years of experience designing interactive exhibitions and learning environments in early childhood centres, schools, and cultural venues. She has a strong interest in the use of design to provoke and support learning in formal and informal settings. The theory and practice of the educational project of Reggio Emilia, Italy has been a constant source of inspiration and challenge. The educators in this remarkable network of schools believe the physical environment has a vital role in children’s social and learning experiences – and that the environment can be a ‘teacher’ in itself.

“What emerges from the material is evidence that children have the capacity to examine critically the normal and everyday spaces in which they learn and can articulate their future in previously unimagined ways.”

THE PROCESS

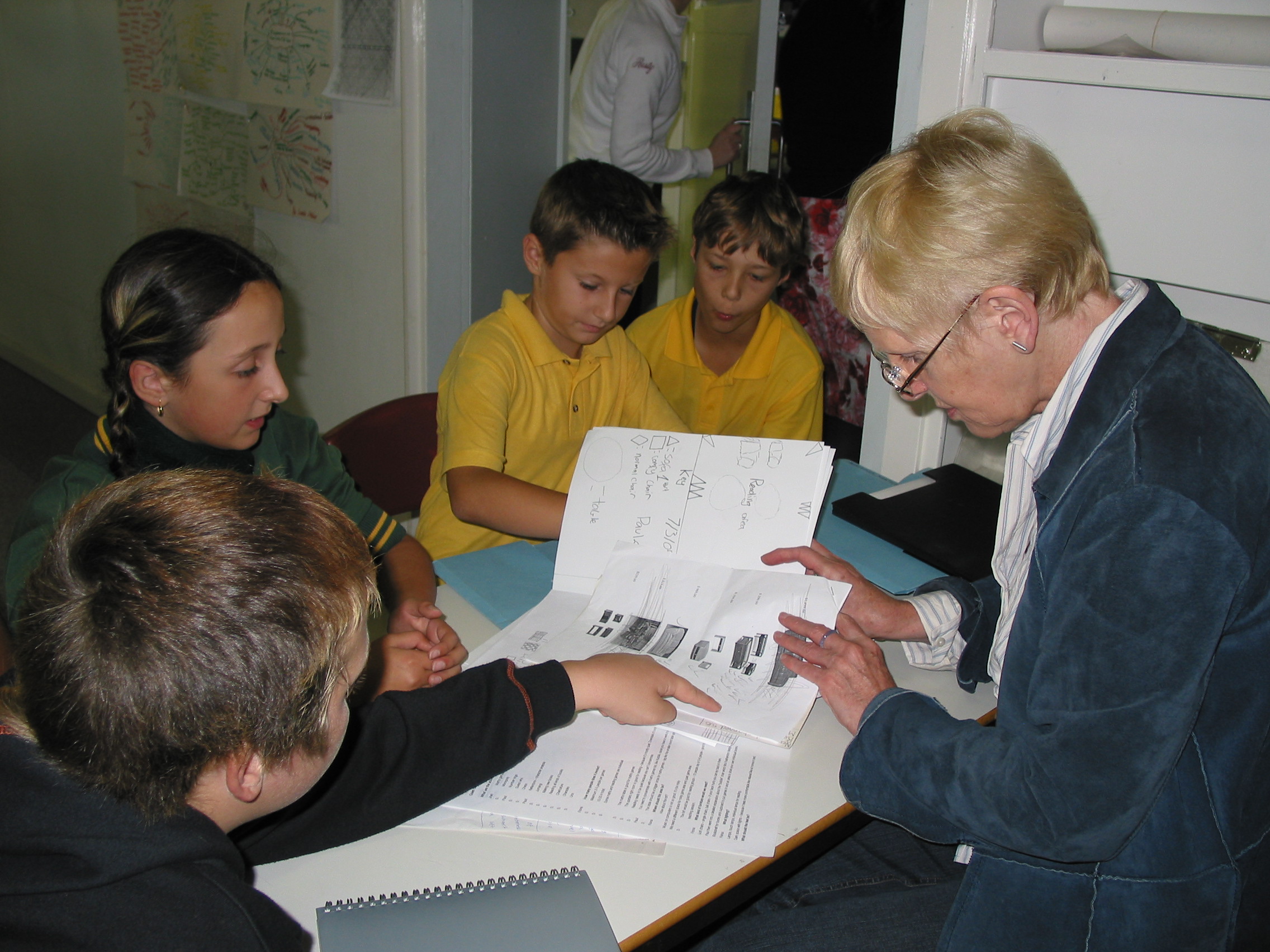

During the first term of 2005 all student and staff in the 5/6 Unit were involved in the design process, from analysis of needs, to assessment of existing space and resources and finally development of design solutions. At the initial meeting, with all school staff, research into children’s perceptions of their physical environment was discussed. Also, surveys of children’s views about school and schooling – from Australia, UK and Scandinavia.

This discussion led to a decision to ask all the students ‘What is it like to be a student at WPPS?’ The children’s responses, in words and drawings, indicate their strong priorities – play and friendships, followed by anything involving activity and comments about the importance of learning and working hard. Students were then invited to name the qualities that were important to them in the environment: friendship, happiness, resilience, respect. To the same question staff nominated: comfort, spaciousness, welcoming, purposeful, interactive, and stimulating. This raises another design challenge: what is an appropriate ambience for a school learning environment: Domestic, corporate, workshop, community centre, children’s museum...?

Working with all the students, we investigated the many functional requirements,including an analysis of the scope and nature of experiences to be provided and the variety of groupings required for each activity. Given that this was to be a highly dynamic and fluid program it was important to ensure that this could be achieved with the resources available: teachers, time and space. Location of students and staff in time and space were charted as ‘snapshots’ in time, how might students and staff be dispersed in the environment – would there be enough space and things to do? Would staff be available to fulfill all their many roles – teaching, facilitating, negotiating curriculum, comforting and so on, at any one time. We then took the long list of experiences to be accommodated and categorized them according to those with similar functional requirements e.g. those requiring a permissive environment for messy activities, quiet, concentrating activities or vigorous, noisy large group activities etc. Which settings require services such as water, power, controlled lighting, computers and network connections? Small teams of students investigated each of these areas in detail with the designer – discussing ideas, investigating (online and excursions), proposing design ideas (descriptions, photos, drawings, models). In some areas – classroom, study, personal storage – the children were brimming with ideas, but in others they had little experience to draw on, so small group excursions were taken to workshops, a creative office environment, a broadcasting studio, a furniture factory, a performance space, and a discovery centre. Documentation of the design process was displayed in the Unit and is now archived.

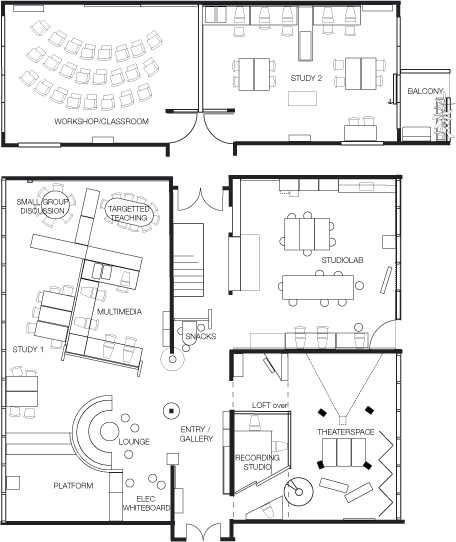

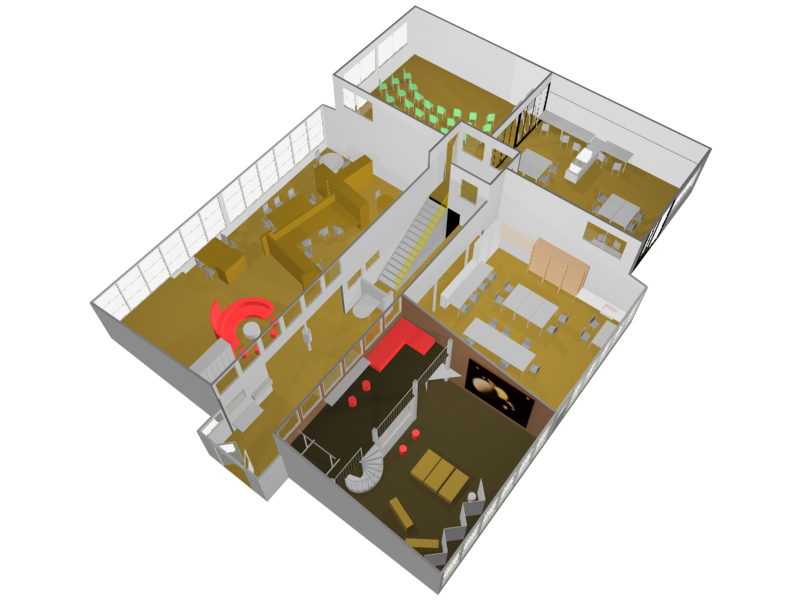

THE DESIGN

The refurbished Unit melds together areas that are traditionally provided separately –general learning areas and specialist facilities. The overall Unit comprises fifteen discrete, dedicated settings each supporting a particular activity but all interlinked – a flowing space for people and the cross-fertilisation of ideas. This spatial arrangement enables students as individuals and groups to move seamlessly between areas in the course of developing on-going projects – eliminating the wait for scheduled sessions in remote specialist facilities. The approach taken to design was tempered by the fact that these are very busy environments, full of people, movement and things. Design is concerned not only with how well an environment functions but also how it ‘feels’ – the ambience or psychological affect. In contemporary architecture this is often a strong expression of a current design idiom. But in this case, an educational setting, design needs to play a subtle role – helping to clarify, harmonise and focus attention on the children and their works. The physical environment is then an ‘intelligent’ collaborator rather than an imposition of ‘design for design’s sake.’ Even intangible values such as ‘democracy’ and ‘respect’may be evoked in the physical environment by spatial planning, design and arrangement of furniture etc. The completed refurbishment provides a diverse, but stable environment. There is flexibility within most areas e.g. the drama space may be readily converted from a totally blacked out space for a/v presentations to an open space for movement and music. But total flexibility (of the whole Unit), which is often seen as the ‘future proof’ solution, was regarded as an impediment and an inefficient use of teacher’s precious time and energy. Also, such temporary settings often fail to adequately support the activity. Stability of the environment enables everyone to know where things are kept, where to go for a particular activity and to evolve the rich possibilities of each setting.

“The new Unit works well – I don’t have to waste my time setting up for activities any more – the students can just move straight into whatever they plan to do.”

The design process itself was a response to the school’s belief that children must be respected and their voices be actively listened to – all the students were involved in a highly participatory design process over several weeks. Their ideas influenced many aspects of design and led to the inclusion of a central drinking fountain, chairs with writing tablets, theatre lighting, angled drawing boards, computers in all areas, artefact drawers, new locker design etc.

As with the complexity of learning processes where everything affects everything else – so every aspect of the physical environment interacts together and it is that richness and complexity of interconnection which this report seeks to illustrate. For example, some items of furniture perform multiple functions: lockers for children’s personal storage were designed for tidy storage, for display (the rear surfaces provide a variety of display possibilities, and to provide substantial spatial division throughout the Unit.

“It doesn’t look at all like a school – it feels like home. ”

Multiple postures are accommodated including relaxed, convivial seating, ergonomic task seating, sitting and standing height work surfaces of different sizes and shapes and unobstructed floor space for vigorous activities.

One of the challenges of such a participatory design project is the lack of a shared vocabulary, the following descriptors embody concepts of relationships, learning and design:

A communal environment – a unified, shared space to support and reflect a democratic community of learners – children and adults

A diverse environment – discrete but inter-linked settings to support a wide variety of social and learning experiences – diversity is more useful than flexibility.

A purposeful environment – rich, complex settings that provide cues for use

A respectful environment – acknowledging children as capable, competent and curious – each with unique life experiences

An autonomous environment – design to enable children to self-manage and negotiate their curriculum

A playful environment – an appropriate ambience which recognises children’s priorities for play and friendships

An aesthetic environment – children deserve harmony, beauty and a high quality environment

A realistic environment – modest design, utilising the potential of the existing building

A responsive environment – contemporary design incorporating contemporary, responsive technology

An evolving environment – a responsive, changing environment – well maintained, evaluated, modified and enriched

“People listen to my ideas. Different spaces help me to learn new things.”

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There are many impediments to the translation of schools from conventional instructional classrooms to convivial learning environments: a general lack of awareness of the role of the physical environment, lack of shared language between educators and design professionals, lack of appropriate design processes involving all protagonists. This project sought to explore solutions.

In the refurbished environment, pedagogy and design are inseparably linked. Anecdotal evidence is being collected from all the participants and visitors – of whom there have been many from state and private, primary and secondary schools, teachers in training, bureaucrats, academics and design professionals.

“ …it is no longer a matter of improving known types of school, but of calling their design into question in order to invent new educational tools and integrate them into sets of facilities of hitherto unattained complexity.”

The physical environment has been a hidden character in the story of schools and schooling. This project demonstrates that rich learning experiences are as much about provision of loose items – the real stuff of learning – as it is about the built spaces and furnishing.

A master plan for the school was prepared as part of this project and is informing all future developments. Schools are dynamic, evolving organisms, and the physical environment should be the subject of continuous evaluation, innovation and evolution.